Where rare seabirds breed - Sunday May 19th 2001

By Deborah McIntosh - The Illawarra Mercury

Few people will ever set foot on Wollongong's Five Islands, but after talking to National Parks and Wildlife NSW ranger Jamie Erskine, you'd be happy to leave it to the birds. Mr Erskine has landed on the islands 10 times in the past two years, and has suffered minor injuries every second time. There were no safe landing spots, he said. Even the only beach, on Big Island, is treacherous. As soon as you're out of the boat you have to drag it on land at lightning speed, before the waves pound it in."Once I was on the front of the boat waiting to jump off and we hit a rock and I

Public safety is one reason why the NPWS doesn't allow the general public on the islands without a permit. But there's another, some would say, more important one.The Five Islands - Big, Martin, Rocky, Bass and Flinders (also known as Toothbrush) - are actually a nature reserve, managed by the NPWS. This means they have a high conservation value, and the reason is birds.Every year thousands of seabirds and shorebirds flock to the islands to breed. These include common gulls and shearwaters, and the rare sooty oystercatcher.There are just 200 sooty oystercatchers in NSW and 19 pairs nest on Five Islands, about 30 per cent of the breeding population.Southern Oceans Seabird Study Association (SOSSA) president Lindsay Smith has been visiting the islands to monitor bird numbers for 33 years, and is still in awe of the natural world he encounters there."The amazing paradox is that you have some of the largest breeding seabird colonies in NSW right on the doorstep of one of the largest industrial complexes in the southern hemisphere" he said."When we're working on the islands at night, which we do quite a bit, I sit outside our little hut out there and look back at the industrial complex and I just cannot comprehend the paradox of it all."

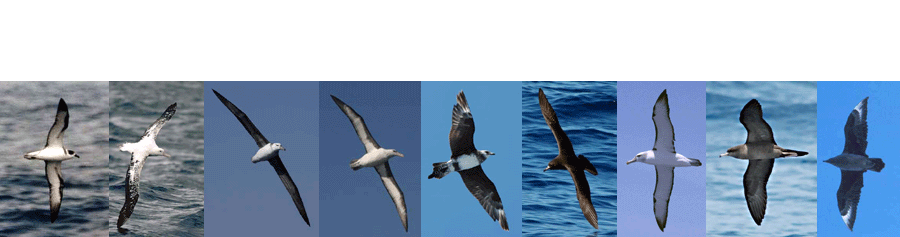

Mr Smith, of Unanderra, knows the Five Islands better than just about anyone. Now retired, he was a ``hydraulics engineer by trade, and a marine ornithologist by choice''.He helped found SOSSA, a highly regarded association run by volunteers. SOSSA not only has a permit to work on the islands but also to have a hut on Big Island for overnight stays.When David Attenborough and his team came to the Illawarra in 1997 to film albatrosses for the series, The Life of Birds, they turned to SOSSA, which also does a lot of albatross research. Even the NPWS referred Weekender to Mr Smith as the authority on birds on Five Islands.

After the sooty oystercatcher, the next rarest bird was the kelp gull, Mr Smith said. It's a large black-backed gull often confused with the albatross.The state's population is less than 200 and 35 pairs nested on the islands last year, mainly on Bass with some on Flinders.Up to 2000 pairs of crested terns breed on the islands, and around 5000 pairs of wedge-tailed shearwaters and 200 pairs of short-tailed shearwaters. Up to 1200 pairs of pelicans breed year round, with a maximum of 300 pairs at a time.Mr Smith is unsure of little penguin numbers: "Three years ago they were devastated by a lack of food, and we lost nearly 90 per cent of the population. But last year they had a successful season."There's probably 500 pairs now. They nest from mid July through to February.''About 150 pairs of white-faced storm petrels nest on Flinders. They used to

The biggest change on the islands, since Mr Smith started visiting them in 1968, has been with vegetation."The islands are in a disgraceful condition,'' he said. The degeneration is due to cattle, which grazed on Big Island in the late 1800s and the introduction of weeds such as kikuyu and bitou bush."Kikuyu first appeared in 1968/69. We're not sure how it got there. It's taken over most of the islands now and has had a profound effect on the breeding seabirds because birds such as penguins and shearwaters are burrowing birds - they lay their eggs underground."The kikuyu is becoming so thick that the birds become entangled in it and die.''Almost three years ago, the NPWS, SOSSA and the local Coomaditchie Aboriginal community received a $18,600 grant for a regeneration project, but little work has yet taken place. Mr Smith said the grant was under the control of NPWS and that they had been dragging the chain. Ranger Jamie Erskine said the project had been in abeyance because the project manager left, ``but we've appointed another person to that position so it will continue''. The objective will be to remove weeds and replace them with natural vegetation.Mr Erskine said the NPWS had taken botanists to Big Island to see what native vegetation remained and how it could be encouraged to grow. The NPWS often worked with university researchers, he said."We've always had two or three (university) projects on the go (involving Five Islands). They span all disciplines under the environmental sciences degree, such as geosciences and biological sciences.''

Mr Smith, his wife Janice Jenkin and other SOSSA volunteers visit the islands 15 to 20 times a year. Mostly they land on the beach at Big Island, but even there landing can be difficult; sometimes they have to return to the mainland if the conditions aren't just right.Volunteers work in one or two groups of three. One person catches the birds, one bands them (attaching a metal band with a serial number to their leg) and one records details."When these birds are found elsewhere in Australia or overseas, people report the band number to the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. That way we can work out the dispersal of the birds and how long they live,'' Mr Smith said.SOSSA teams stay overnight in the spartan hut, easily seen from Hill 60. No-one else is permitted to use it.A few years ago vandals trashed it and stole about $2000 worth of gear. Until then, SOSSA members had sometimes turned a blind eye to the fact that people had been on the island. If they spot someone now they invariably call the NPWS, which can impose hefty fines.

"A number of people have been fined around $3500,'' Mr Smith said. "The volunteer coast guard at Hill 60 monitors the island. In the past, fishermen were out there (on Big Island) every weekend, but it's down to one or two times a year now.'' People are allowed to approach the islands by boat and fish around them.So why do birds breed on Five Islands?"They're seabirds and shorebirds which get their tucker from the ocean or the rocks. And it's safe,'' Mr Erskine said. "If those populations were on the mainland they'd be constantly being picked off by humans and cats and dogs, and having their vegetation burnt and cleared. Out there, they're protected."There are birds that may not breed if people go out there,'' he added. "If you disturb animals like pelicans, they'll just take off and leave their young to starve.

"And if people are traipsing across thick kikuyu, they might be actually bouncing on the bodies of baby birds. Humans have a great impact on the planet and some of these areas just need to be left alone as refuges so birds and animals can continue to exist.''

Sections

Sections Calendar

Calendar