In 1956 the CSIRO created the Australian Bird Banding Scheme as a facility for use by professional and amateur scientists. Two naturalists,

W.L.N.(Lance) Tickell of Bristol, UK, managed to get to South Georgia in 1958, where he was to pursue a Ph.D studying Wandering Albatrosses for 3 years. He found his first Australian band on 29 December 1958, the first real evidence of the great distances travelled by these masters of flight. On 18 July 1959, the first of Lance Tickell's bands was recovered off Wollongong, and many more recoveries were to come. In 1958, another group, initially S.G.(Bill) Lane, M.D.(Durno) Murray and C.B.(Clive) Campion, commenced banding great albatrosses that frequented one of Sydney's ocean sewer outfalls (Malabar). It was not long before they too were exchanging bands with Lance. The provenance of some 500 visitors to New South Wales has now been established, representing the majority of great albatross breeding colonies.

Some of the pioneers in this work have since passed on but some of the birds that they banded as far back as 1959 still return regularly to forage off Wollongong.

Current status of great albatrosses off Wollongong

In 1970, following the commissioning of a treatment plant, the Malabar sewage no longer held any attraction and a decline in the number of great

The attraction

A large cuttlefish, Sepia apama, is widespread in the coastal waters of southern Australia. In common with other cephalopods, it quickly grows to maturity (2 years for this species) breeds once and then dies. Breeding is virtually synchronous, with adults dying over the period July-August in central New South Wales. The start of the mortality becomes progressively later with increasing latitude, thus albatrosses can forage possibly until November on this resource by following the mortality wave southwards. Cuttlefish carcasses (up to 15kg) float and become food for all of the local marine carnivores, including albatrosses and other seabirds. For some reason, probably the topography of the sea floor, the cuttlefish population off Wollongong is exceptional and hundreds of carcasses can be seen in some years. While several studies have suggested that great albatrosses prefer to frequent pelagic (beyond the continental shelf break) waters, at Wollongong they make an exception and some individuals have approached to within 1 metre of the shore.

Current Studies:

Provenance and Sexing

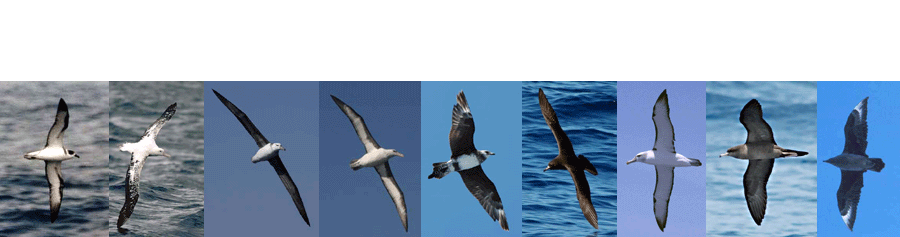

With the exception of Royal and Amsterdam Albatrosses, great albatrosses from all known breeding islands have been encountered at Wollongong. As birds from diverse colonies and of either sex in an aggregation are morphologically similar, it is usually not possible to determine sex or

Energetics and Nutrition

It is clear that there is an important association between albatrosses and the cuttlefish, Sepia apama. Birds visiting Wollongong are, with perhaps the odd exception, are either non-breeders or those not currently breeding. For albatrosses, breeding is energetically very demanding; between breeding bouts they need to regain body condition and replace worn feathers. Wollongong, where forage is accessible with minimal energy expenditure is probably an ideal location to undertake this recovery process.

Research into nutritional and energetic relationships between albatrosses and the cuttlefish is a project now into its 6th year.

Other Albatross Projects:

Comparative Physiology

With the availability of several species of albatrosses and the close proximity of research facilities, a rare combination, the opportunity to undertake comparative physiological studies has been seized. This is another collaborative project with the University of Wollongong and is finding some interesting energetic relationships within the albatross guild.

Sections

Sections Calendar

Calendar